Ontologies are the structural frameworks for organizing information on the semantic Web and within semantic enterprises. They provide unique benefits in discovery, flexible access, and information integration due to their inherent connectedness; that is, their ability to represent conceptual relationships. Ontologies can be layered on top of existing information assets, which means they are an enhancement and not a displacement for prior investments. And ontologies may be developed and matured incrementally, which means their adoption may be cost-effective as benefits become evident [1].

What Is an Ontology?

Ontology may be one of the more daunting terms for those exposed for the first time to semantic technologies. Not only is the word long and without common antecedents, but it is also a term that has widely divergent use and understanding within the community. It can be argued that this not-so-little word is one of the barriers to mainstream understanding of the semantic Web.

The root of the term is the Greek ontos, or being or the nature of things. Literally — and in classical philosophy — ontology was used in relation to the study of the nature of being or the world, the nature of existence. Tom Gruber, among others, made the term popular in relation to computer science and artificial intelligence about 15 years ago when he defined ontology as a “formal specification of a conceptualization.”

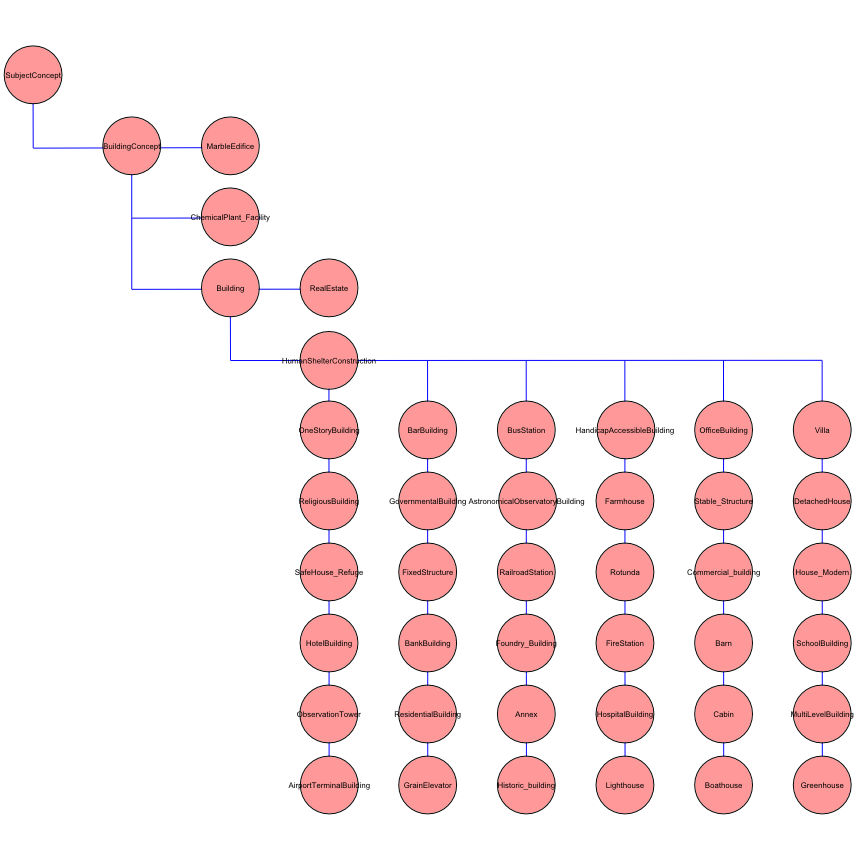

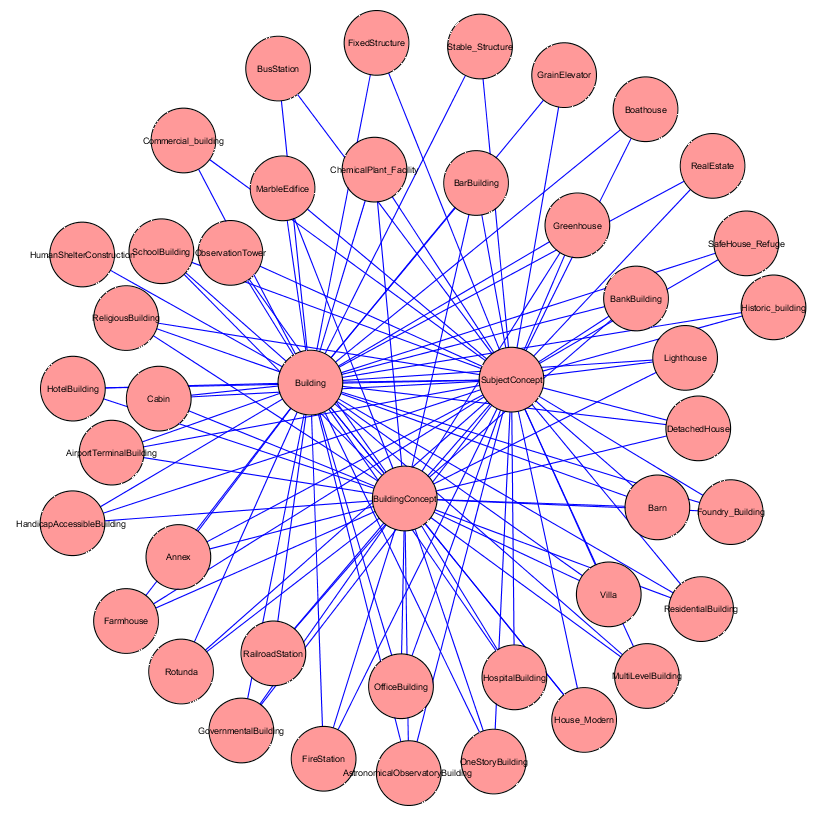

Much like taxonomies or relational database schema, ontologies work to organize information. No matter what the domain or scope, an ontology is a description of a world view. That view might be limited and miniscule, or it might be global and expansive. However, unlike those alternative hierarchical views of concepts such as taxonomies, ontologies often have a linked or networked “graph” structure. Multiple things can be related to other things, all in a potentially multi-way series of relationships.

|

|

|

| A distinguishing characteristic of ontologies compared to conventional hierarchical structures is their degree of connectedness, their ability to model coherent, linked relationships |

||

Ontologies supply the structure for relating information to other information in the semantic Web or the linked data realm. Ontologies thus provide a similar role for the organization of data that is provided by relational data schema. Because of this structural role, ontologies are pivotal to the coherence and interoperability of interconnected data.

When one uses the idea of “world view” as synonomous with an ontology, it is not meant to be cosmic, but simply a way to convey how a given domain or problem area can be described. One group might choose to describe and organize, say, automobiles, by color; another might choose body styles such as pick-ups or sedans; or still another might use brands such as Honda and Ford. None of these views is inherently “right” (indeed multiples might be combined in a given ontology), but each represents a particular way — a “world view” — of looking at the domain.

Though there is much latitude in how a given domain might be described, there are both good ontology practices and bad ones. We offer some views as to what constitutes good ontology design and practice in the concluding section.

What Are Its Benefits?

A good ontology offers a composite suite of benefits not available to taxonomies, relational database schema, or other standard ways to structure information. Among these benefits are:

- Coherent navigation by enabling the movement from concept to concept in the ontology structure

- Flexible entry points because any specific perspective in the ontology can be traced and related to all of its associated concepts; there is no set structure or manner for interacting with the ontology

- Connections that highlight related information and aid and prompt discovery without requiring prior knowledge of the domain or its terminology

- Ability to represent any form of information, including unstructured (say, documents or text), semi-structured (say, XML or Web pages) and structured (say, conventional databases) data

- Inferencing, whereby by specifying one concept (say, mammals) one knows that we are also referring to a related concept (say, that mammals are a kind of animal)

- Concept matching, which means that even though we may describe things somewhat differently, we can still match to the same idea (such as glad or happy both referring to the concept of a pleasant state of mind)

- Thus, this means that we can also integrate external content by proper matching and mapping of these concepts

- A framework for disambiguation by nature of the matching and analysis of concepts and instances in the ontology graph, and

- Reasoning, which is the ability to use the coherence and structure itself to inform questions of relatedness or to answer questions.

How Are Ontologies Used?

The relationship structure underlying an ontology provides an excellent vehicle for discovery and linkages. “Swimming through” this relationship graph is the basis of the Concept Explorer (also known as the Relation Browser) and similar widgets.

The most prevalent use of ontologies at present is in semantic search. Semantic search has benefits over conventional search in terms of being able to make inferences and matches not available to standard keyword retrieval.

The relationship structure also is a powerful and more general and more nuanced way to organize information. Concepts can relate to other concepts through a richness of vocabulary. Such predicates might capture subsumption, precedence, parts of relationships (mereology), preferences, or importances along virtually any metric. This richness of expression and relationships can also be built incrementally over time, allowing ontologies to grow and develop in sophistication and use as desired.

The pinnacle application for ontologies, therefore, is as coherent reference structures whose purpose is to help map and integrate other structures and information. Given the huge heterogeneity of information both within and without organizations, the use of ontologies as integration frameworks will likely emerge as their most valuable use.

What Makes for a Good Ontology?

Good ontology practice has aspects both in terms of scope and in terms of construction.

Scope Considerations

Here are some scoping and design questions that we believe should be answered in the positive in order for an ontology to meet good practice standards:

- Does the ontology provide balanced coverage of the subject domain? This question gets at the issue of properly scoping and bounding the subject coverage of the ontology. It also means that the breadth and depth of the coverage is roughly equivalent across its scope

- Does the ontology embed its domain coverage into a proper context? A major strength of ontologies is their potential ability to interoperate with other ontologies. Re-using existing and well-accepted vocabularies and including concepts in the subject ontology that aid such connections is good practice. The ontology should also have sufficient reference structure for guiding the assignment of what content “is about”

- Are the relationships in the ontology coherent? The essence of coherence is that it is a state of logical, consistent connections, a logical framework for integrating diverse elements in an intelligent way. So while context supplies a reference structure, coherence means that the structure makes sense. Is the hip bone connected to the thigh bone, or is the skeleton incorrect?

- Has the ontology been well constructed according to good practice? See next.

If these questions can be answered affirmatively, then we would deem the ontology ready for production-grade use.

Fundamental to the whole concept of coherence is the fact that experts and practitioners within domains have been looking at the questions of relationships, structure, language and meaning for decades. Though perhaps today we now finally have a broad useful data and logic model in RDF, the fact remains that massive time and effort has already been expended to codify some of these understandings in various ways and at various levels of completeness and scope. Good practice also means, therefore, that maximum leverage is made to springboard ontologies from existing structural and vocabulary assets.

And, because good ontologies also embrace the open world approach, working toward these desired end states can also be incremental. Thus, in the face of common budget or deadline constraints, it is possible initially to scope domains as smaller or to provide less coverage in depth or to use a small set of predicates, all the while still achieving productive use of the ontology. Then, over time, the scope can be expanded incrementally.

Construction Considerations

To achieve their purposes, ontologies must be both human-readable and machine-processable. Also, because they represent conceptual structures, they must be built with a certain composition.

Good ontologies therefore are constructed such that they have:

- Concept definitions – the matching and alignment of things is done on the basis of concepts (not simply labels) which means each concept must be defined

- A preferred label that is used for human readable purposes and in user interfaces

- A “semset” – which means a series of alternate labels and terms to describe the concept. These alternatives include true synonyms, but may also be more expansive and include jargon, slang, acronyms or alternative terms that usage suggests refers to the same concept

- Clearly defined relationships (also known as properties, attributes, or predicates) for relating two things to one another

- All of which is written in a machine-processable language such as OWL or RDF Schema (among others).

In the case of ontology-driven applications using adaptive ontologies, there are also additional instructions contained in the system (often via administrative ontologies) that tell the system which types of widgets need to be invoked for different data types and attributes. This is different than the standard conceptual schema, but is nonetheless essential to how such applications are designed.