The Reality is: Most Connections are Proximate

The Reality is: Most Connections are Proximate

What does it mean to interoperate information on the Web? With linked data and other structured data now in abundance, why don’t we see more information effectively combined? Why express your information as linked data if no one is going to use it?

Interoperability comes down to the nature of things and how we describe those things or quite similar things from different sources. This was the major thrust of my recent keynote presentation to the Dublin Core annual conference. In that talk I described two aspects of the semantic “gap”:

- One aspect is the need for vetted reference sources that provide the entities and concepts for aligning disparate content sources on the Web, and

- A second aspect is the need for accurate mapping predicates that can represent the often approximate matches and overlaps of this heterogeneous content.

I’ll discuss the first “gap” in a later post. What we’ll discuss here is the fact that most relationships between putatively same things on the Web are rarely exact, and are most often approximate in nature.

“It Ain’t the Label, Mabel”

The use of labels for matching or descriptive purposes was the accepted practice in early libraries and library science. However, with the move to electronic records and machine bases for matching, appreciation for ambiguities and semantics have come to the fore. Labels are no longer an adequate — let alone a sufficient — basis for matching references.

The ambiguity point is pretty straightforward. Refer to Jimmy Johnson by his name, and you might be referring to a former football coach, a NASCAR driver, a former boxing champ, a blues guitarist, or perhaps even a plumber in your home town. Or perhaps none of these individuals. Clearly, the label “Jimmy Johnson” is insufficient to establish identity.

Of course, not all things are named entities such as a person’s name. Some are general things or concepts. But, here, semantic heterogeneities can also lead to confusion and mismatches. It is always helpful to revisit the sources and classification of semantic heterogeneities, which I first discussed at length nearly five years ago. Here is a schema classifying more than 40 categories of potential semantic mismatches [1]:

| Class | Category | Subcategory |

| STRUCTURAL | Naming | Case Sensitivity |

| Synonyms | ||

| Acronyms | ||

| Homonyms | ||

| Generalization / Specialization | ||

| Aggregation | Intra-aggregation | |

| Inter-aggregation | ||

| Internal Path Discrepancy | ||

| Missing Item | Content Discrepancy | |

| Attribute List Discrepancy | ||

| Missing Attribute | ||

| Missing Content | ||

| Element Ordering | ||

| Constraint Mismatch | ||

| Type Mismatch | ||

| DOMAIN | Schematic Discrepancy | Element-value to Element-label Mapping |

| Attribute-value to Element-label Mapping | ||

| Element-value to Attribute-label Mapping | ||

| Attribute-value to Attribute-label Mapping | ||

| Scale or Units | ||

| Precision | ||

| Data Representation | Primitive Data Type | |

| Data Format | ||

| DATA | Naming | Case Sensitivity |

| Synonyms | ||

| Acronyms | ||

| Homonyms | ||

| ID Mismatch or Missing ID | ||

| Missing Data | ||

| Incorrect Spelling | ||

| LANGUAGE | Encoding | Ingest Encoding Mismatch |

| Ingest Encoding Lacking | ||

| Query Encoding Mismatch | ||

| Query Encoding Lacking | ||

| Languages | Script Mismatches | |

| Parsing / Morphological Analysis Errors (many) | ||

| Syntactical Errors (many) | ||

| Semantic Errors (many) | ||

Even with the same label, two items in different information sources can refer generally to the same thing, but may not be the same thing or may define it with a different scope and content. In broad terms, these mismatches can be due to structure, domain, data or language, with many nuances within each type.

The sameAs approach used by many of the inter-dataset linkages in linked data ignores these heterogeneities. In a machine and reasoning sense, indeed even in a linking sense, these assertions can make as little or nonsensical sense as talking about the plumber with the facts about the blues guitarist.

Cats, Paul Newman and Great Britain

Let’s take three examples where putatively we are talking about the same thing and linking disparate sources on the Web.

The first example is the seemingly simple idea of “cats”. In one source, the focus might be on house cats, in another domestic cats, and in a third, cats as pets. Are these ideas the same thing? Now, let’s bring in some taxonomic information about the cat family, the Felidae. Now, the idea of “cats” includes lynx, tigers, lions, cougars and many other kinds of cats, domestic and wild (and, also extinct!). Clearly, the “cat” label used alone fails us miserably here.

Another example is one that Fred Giasson and I brought up one year ago in When Linked Data Rules Fail [2]. That piece discussed many poor practices within linked data, and used as one case the treatment of articles in the New York Times about the (deceased) actor Paul Newman. The NYT dataset is about various articles written about people historically in the newspaper. Their record about Paul Newman was about their pool of articles with attributes such as first published and so forth, with no direct attribute information about Paul Newman the person. Then, they asserted a sameAs relationship with external records in Freebase and DBpedia, which acts to commingle person attributes like birth, death and marriage with article attributes such as first and last published. Clearly, the NYT has confused the topic ( Paul Newman) of a record with the nature of that record (articles about topics). This misunderstanding of the “thing” at hand makes the entailed assertions from the multiple sources illogical and useless [3].

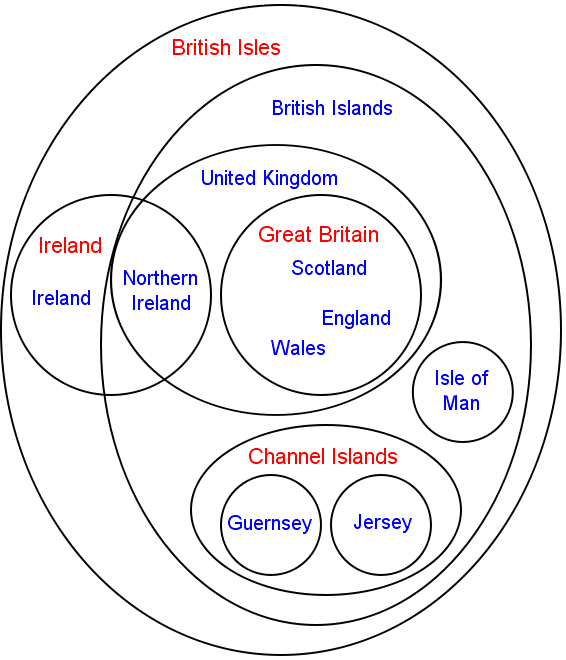

Our third example is the concept or idea or named entity of Great Britain. Depending on usage and context, Great Britain can refer to quite different scopes and things. In one sense, Great Britain is an island. In a political sense, Great Britain can comprise the territory of England, Scotland and Wales. But, even more precise understandings of that political grouping may include a number of outlying islands such as the Isle of Wight, Anglesey, the Isles of Scilly, the Hebrides, and the island groups of Orkney and Shetland. Sometimes the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands, which are not part of the United Kingdom, are fallaciously included in that political grouping. And, then, in a sporting context, Great Britain may also include Northern Ireland. Clearly, these, plus other confusions, can mean quite different things when referring to “Great Britain.” So, without definition, a seemingly simple question such as what the population of Great Britain is could legitimately return quite disparate values (not to mention the time dimension and how that has changed boundaries as well!).

These cases are quite usual for what “things” mean when provided from different sources with different perspectives and with different contexts. If we are to get meaningful interoperation or linkage of these things, we clearly need some different linking predicates.

Some Attempts at ‘Approximateness’

The realization that many connections across datasets on the Web need to be “approximate” is growing. Here is the result of an informal survey for leading predicates in this regard [4]:

|

|

|

Besides the standard OWL and RDFS predicates, SKOS, UMBEL and DOLCE [5] provide the largest number of choices above. In combination, these predicates probably provide a good scoping of “approximateness” in mappings.

Rationality and Reasoners

It is time for some leadership to emerge to provide a more canonical set of linking predicates for these real-world connection requirements. It would also be extremely useful to have such a canonical set adopted by some leading reasoners such that useful work could be done against these properties.

I’ve been interested/concerned about this for a long time, thanks for bringing it up again. I think it highlights one of the fundamental problems with knowledge representation on the semantic web- exactly as you say “The Reality is: Most Connections are Proximate” but we (and our tools) like to ignore that reality because it makes things more complex. The current described performance of the Pronto reasoner from the Pellet folks which “does not scale beyond a dozen or so conditional constraints” provides a good indication of the added complexity. Nonetheless, it has to be dealt with!