“We’re Successful When We’re Not Needed”

Structured Dynamics has been engaged in open source software development for some time. Inevitably in each of our engagements we are asked about the viability of open source software, its longevity, and what the business model is behind it. Of course, I appreciate our customers seemingly asking about how we are doing and how successful we are. But I suspect there is more behind this questioning than simply good will for our prospects.

Besides the general facts that most of us know — of hundreds of thousands of open source projects only a miniscule number get traction — I think there are broader undercurrents in these questions. Even with open source, and even with good code documentation, that is not enough to ensure long-term success.

When open source broke on the scene a decade or so ago [1], the first enterprise concerns were based around code quality and possible “enterprise-level” risks: security, scalability, and the fact that much open source was itself LAMP-based. As comfort grew about major open source foundations — Linux, MySQL, Apache, the scripting languages of PHP, Perl and Python (that is the very building blocks of the LAMP stack) — concerns shifted to licensing and the possible “viral” effects of some licenses to compromise existing proprietary systems.

Today, of course, we see hugely successful open source projects in all conceivable venues. Granted, most open source projects get very little traction. Only a few standouts from the hundreds of thousands of open source projects on big venues like SourceForge and Google Code or their smaller brethren are used or known. But, still, in virtually every domain or application area, there are 2-3 standouts that get the lion’s share of attention, downloads and use.

I think it fair to argue that well-documented open source code generally out-competes poorly documented code. In most circumstances, well-documented open source is a contributor to the virtuous circle of community input and effort. Indeed, it is a truism that most open source projects have very few code committers. If there is a big community, it is largely devoted to documentation and assistance to newbies on various forums.

I think it fair to argue that well-documented open source code generally out-competes poorly documented code. In most circumstances, well-documented open source is a contributor to the virtuous circle of community input and effort. Indeed, it is a truism that most open source projects have very few code committers. If there is a big community, it is largely devoted to documentation and assistance to newbies on various forums.

We see some successful open source projects, many paradoxically backed by venture capital, that employ the “package and document” strategy. Here, existing open source pieces are cobbled together as more easily installed comprehensive applications with closer to professional grade documentation and support. Examples like Alfresco or Pentaho come to mind. A related strategy is the “keystone” one where platform players such as Drupal, WordPress, Joomla or the like offer plug-in architectures and established user bases to attract legions of third-party developers [2].

OK, So What Has This to Do with the Enterprise?

I think if we stand back and look at this trajectory we can see where it is pointing. And, where it is pointing also helps define what the success factors for open source may be moving forward.

Two decades ago most large software vendors made on average 75% to 80% of their revenues from software licences and maintenance fees; quite the opposite is true today [3]. The successful vendors have moved into consulting and services. One only needs look to three of the largest providers of enterprise software of the past two decades — IBM, Oracle and HP — to see evidence of this trend.

How is it that proprietary software with its 15% to 20% or more annual maintenance fees has been so smoothly and profitably replaced with services?

These suppliers are experienced hands in the enterprise and know what any seasoned IT manager knows: the total lifecycle costs of software and IT reside in maintenance, training, uptime and adaptation. Once installed and deployed, these systems assume a life of their own, with actual use lifetimes that can approach two to three decades.

This reality is, in part, behind my standard exhortation about respecting and leveraging existing IT assets, and why Structured Dynamics has such a commitment to semantic technology deployment in the enterprise that is layered onto existing systems. But, this very same truism can also bring insight into the acceptable (or not) factors facing open source.

Great code — even if well documented — is not alone the mousetrap that leads the world to the door. Listen to the enterprise: lifecycle costs and longevity of use are facts.

But what I am saying here is not really all that earthshaking. These truths are available to anyone with some experience. What is possibly galling to enterprises is two smug positions of new market entrants. The first, which is really naïve, is the moral superiority of open source or open data or any such silly artificial distinctions. That might work in the halls of academia, but carries no water with the enterprise. The second, more cynically based, is to wrap one’s business in the patina of open source while engaging in the “wink-wink” knowledge that only the developer of that open source is in a position to offer longer term support.

Enterprises are not stupid and understand this. So, what IT manager or CIO is going to bet their future software infrastructure on a start-up with immature code, generally poor code documentation or APIs, and definitely no clear clue about their business?

The Slow Squeeze

Yet, that being said, neither enterprises nor vendors nor software innovators that want to work with them can escape the inexorable force of open source. While it has many guises from cloud computing to social software or software as a service or a hundred other terms, the slow squeeze is happening. Big vendors know this; that is why there has been the rush to services. Start-up vendors see this; that is why most have gone consumer apps and ad-based revenue models. And enterprises know this, which is why most are doing nothing other than treading water because the way out of the squeeze is not apparent.

The purpose of this three-part series is to look at these issues from many angles. What might the absolute pervasiveness of open source mean to traditional IT functions? How can strategic and meaningful change be effected via these new IT realities in the enterprise? And, how can software developers and vendors desirous of engaging in large-scale initiatives with enterprises find meaningful business models?

Lead-in to the Series: a Total Open Solution

And, after we answer those questions, we will rest for a day.

But, no, seriously, these are serious questions.

There is no doubt open source is here to stay, yet its maturity demands new thinking and perspectives. Just as enterprises have known that software is only the beginning of decades-long IT commitments and (sometimes) headaches, the purveyors and users of open source should recognize the acceptance factors facing broad enterprise adoption and reliance.

Open source offers the wonderful prospect of avoiding vendor “lock-in”. But, if the full spectrum of software use and adoption is also not so covered, all we have done is to unlock the initial selection and install of the software. Where do we turn for modifications? for updates? for integration with other packages? for ongoing training and maintenance? And, whatever we do, have we done so by making bets on some ephemeral start-up? (We know how IBM will answer that question.)

The first generation of open source has been a substitute for upfront proprietary licenses. After that, support has been a roll of the dice. Sure, broadly accepted open source software provides some solace because of more players and more attention, but how does this square with the prospect of decades of need?

The perverse reality in these questions is that most all early open source vendors are being gobbled up or co-opted by the existing big vendors. The reward of successful market entry is often a great sucking sound to perpetuate existing concentrations of market presence. In the end, how are enterprises benefiting?

Now, on the face of it, I think it neither positive nor negative whether an early open source firm with some initial traction is gobbled up by a big player or not. After all, small fish tend to be eaten by big fish.

But two real questions arise in my mind: One, how does this gobbling fix the current dysfunction of enterprise IT? And, two, what is a poor new open source vendor to do?

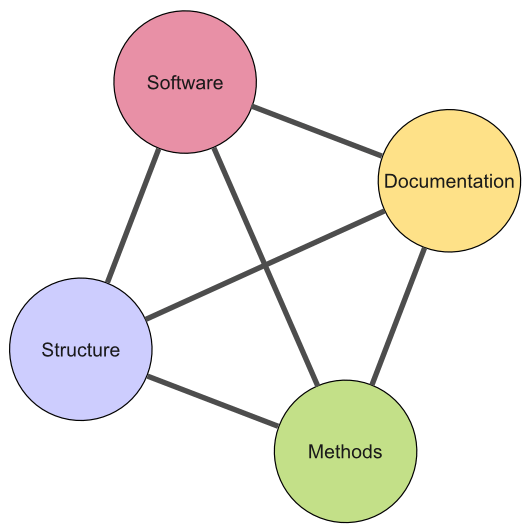

The answer to these questions resides in the concerns and anxieties that caused them to be raised in the first place. Enterprises don’t like “lock-in” but like even less seeing stranded investments. For open source to be successful it needs to adopt a strategy that actively extends its traditional basis in open code. It needs to embrace complete documentation, provision of the methods and systems necessary for independent maintenance, and total lifecycle commitments. In short, open source needs to transition from code to systems.

We call this approach the total open solution. It involves — in addition to the software, of course — recipes, methods, and complete documentation useful for full-life deployments. So, vendors, do you want to be an enterprise player with open source? Then, embrace the full spectrum of realities that face the enterprise.

“We’re Successful When We’re Not Needed”

The actual mantra that we use to express this challenge is, “We’re Successful When We’re Not Needed“. This simple mental image helps define gaps and tells us what we need to do moving forward.

The basic premise is that any taint of lock-in or not being attentive to the enterprise customer is a potential point of failure. If we can see and avoid those points and put in place systems or whatever to overcome them, then we have increased comfort in our open source offerings.

Like good open source software, this is ultimately a self-interest position to take. If we can increase comfort in the marketplace that they can adopt and sustain our efforts without us, they will adopt them to a greater degree. And, once adopted, and when extensions or new capabilities are needed, then as initial developers with a complete grasp on the entire lifecycle challenges we become a natural possible hire. Granted, that hiring is by no means guaranteed. In fact, we benefit when there are many able players available.

In the remaining two parts of this series we will discuss all of the components that make up a total open solution and present a collaboration platform for delivering the methods and documentation portions. We’re pretty sure we don’t yet have it fully right. But, we’re also pretty sure we don’t have it wrong.

Another great post, Michael!

I think the idea of “we’re successful when we’re not needed” is similar to what Douglas Mcllroy once said “As a programmer, it is your job to put yourself out of business. What you do today can be automated tomorrow.”