Notebooks are Only Interactive if You Share

We first began publishing interactive electronic notebooks for this Cooking with Python and KBpedia series in CWPK #16, though the first installment using a notebook started with CWPK #14. I had actually drafted all of the installments up to this one before that date was reached. Since one major purpose of this series was to provide hands-on training, I did not want to force those who wanted to experience some degree of interactivity to have to go through all of the steps to set up their own interactive environment. My hope was that a taste of direct involvement with the code and interactivity would itself encourage users to get more deeply involved to establish their own interactive environments.

I had encountered for myself fully interactive notebooks prior to this point, ones where all I needed to do was to click to operate, so I knew there must be a way to make my own notebooks similarly available. In order to achieve my objective, as is true with so much of this series, I was forced to do the research and discover how I could set up such a thing.

A Survey of the Options

In researching the options it was clear that a spectrum of choices existed. We have already discussed how we can create non-interactive mockups of an interactive notebook using the nbconvert option or converting a drafted notebook using Pandoc (CWPK #15). My research surfaced some additional options to render a notebook page for general Web (HTML) display:

Static Options

nbconvert, but lose interactivity- The Pandoc option

- Publish in other formats (PDF)

- View a non-interactive page via nbviewer by simply providing a URL, which works like

nbconvert.

These options are helpful, of course, but lack the full interactivity desired.

Fully Interactive

Systems that allow code cells to be run interactively are obviously more complex than nice rendering tools. My investigations turned up a number of online services, plus ways to set up own or private servers. From the standpoint of online services, here are the leading options:

There is a Python option that does not provide complete interactivity, but simple interactions of certain aspects of certain notebook cells:

nbinteractis a Python package that provides a command-line tool to generate interactive web pages from Jupyter notebooks

Then, there are a series of online services:

- The MyBinder option, which uses a JupyterHub server directly from a Git repository

- Google’s Colaboratory, which provides a Google flavor on this approach

- Microsoft’s Azure Notebooks, which provides a MS flavor on this approach

- There are other sites such as Kaggle Kernels, CoCalc, nanoHUB, or Datalore that also provide such services, some for a fee.

The other interactive approach is to not use an established service, but to set up your own server.

- For private repositories, one can build on BinderHub, the same technology used by MyBinder, and which runs on JupyterHub running on Kubernetes for most of its functionality, or

- One can run a public notebook server based on Jupyter, though it is limited to a single access user at a time, or

- Set up one’s own JupyterHub, similar to the BinderHub option but not limited to a Git repository.

Frankly, most of the own-server options looked to be too much work simply to support my educational objectives for the CWPK series.

The Chosen MyBinder Option

I was very much committed to have an online service that would run my full stack. I chose to implement the MyBinder option because I could see it worked and was popular, it had close ties to Jupyter and rendered notebooks the same as when using locally, was free, and seemed to have strong backing and documentation. On the other hand, MyBinder has some weaknesses and poses some challenges. Some of the key ones I knew going in or identified as I began working with the system were:

- As a hosted service that runs its applications in containers, it could take some minutes to get the online service active when used after a hiatus, necessary to reconfigure the container specific to the application and Python modules being used

- It reportedly has memory limitation of 1-2 GB. Memory can be an issue with CWPK locally even at the 8 GB level

- The service needed to run off of a Git repo. I had plans to better expose all aspects of the CWPK series and its supporting software on our existing public GitHub repository; the Git requirement caused me to accelerate my exposure of this service

- Though free now, each MyBinder application is a rather large consumer of resources. I have some concerns regarding the longer-term availability of the service

- CWPK would have more than 60 interactive notebook pages, though I did see reference that performance issues may only arise due to multiple, concurrent use. Going in, I had no clue as to what the use factor might be for the service and whether this would pose a problem or not.

Some of these issues deserve their own commentary below.

Setting Up the Environment

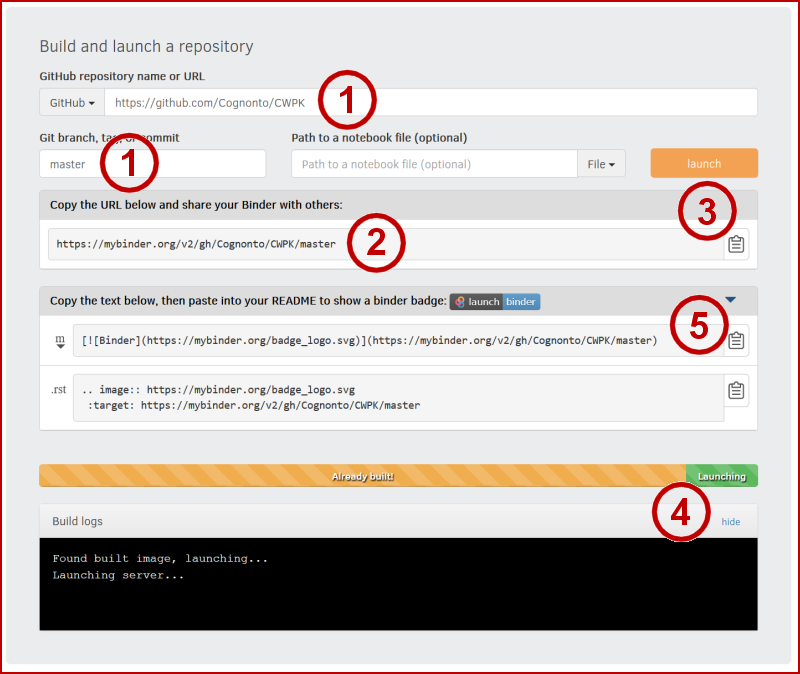

Setting up a new instance at the MyBinder service is relatively straightforward. Here is the basic set-up screen on the main page:

One must first have a Git repository available to start the service. One also needs to have completed an environment configuration file (environment.yml in our case with Python) and a project README.md at the root of the master branch on the repo. In our case, it is the CWPK repository on GitHub; we also indicate we are dealing with the master branch (1). (I had some initial difficulty when I over-specified a link to an individual notebook page; removing this cleared things up.) These simple specifications create the URL that is the link to your formal online project (2). Upon launch (3), the build process is shown to screen (4), which may take some minutes to build. The set of working input specs also provide the basis for generating a link badge you can use on your own Web sites (5).

Upon completion of a successful build, one is shown the standard Jupyter Notebook entry page.

Here are two additional resources useful to setting up a MyBinder application for the first time:

Implementation Challenges

Though set up is straightforward, there are some challenges in implementing MyBinder to accommodate specific CWPK needs. Here are some of the major areas I encountered, and some steps to address them.

Importing Local Code

As has become obvious in our series to date, Python is a highly configurable environment, with literally tens of thousands of packages to choose from to invoke needed functionality. The standard environment settings appear to do a good job of allowing new packages to be specified and imported into the MyBinder system. I had confidence these could be handled appropriately.

My major concern related to CWPK‘s own cowpoke package. At the time of starting this effort, this package was not commercial grade and was not registered on major distribution networks like PyPi or conda-forge. When used locally, including cowpoke is not a big issue: we only need to include it in the local listing of site packages. But, once we rely on a cloud instance, how can we get that code into our online MyBinder system?

The answer, it turns out, is to package our code as one would normally do for a commercial package, and then to include a setup.py configuration file in our local specification. That enables us to invoke the package through the standard MyBinder environment configuration. See especially this key reference and this stub for setup.py.

Local Data Sharing and Organization

Until this point, I had been developing and refining a local file directory structure in which to put different versions of KBpedia, other input files, and example outputs. This system was being developed logically from the perspective of a local file system.

However, these files were local and not exposed for access to an online system like MyBinder. My first thought was to simply copy this structure to the GitHub repo. But the manual copying of files to a version control system is NOT efficient, and the directory structure itself did not appear suitable for a repo presence. Further, manually copying files presents an ongoing issue of keeping local and remote versions in sync. Moreover, as I began adding new daily installments to the GitHub repo, I could see in general that manual additions were not going to be sustainable.

These realizations forced two decisions. First, I would need to re-think and re-organize my directory structures to accommodate both local and repo needs. The directory structure we have developed to date now reflects this re-organization. Second, as described in the next section, I needed to cease my manual use of GitHub and fully embrace it as a version control system.

Fully Embracing GitHub

I have to admit: Every time I try to work with version control with Git, I have been confused and frustrated with how to actually get anything done. I have, hopefully, progressed a bit beyond this point, but I would caution some of you looking to move into this area that you may have to overcome poor documentation and obfuscated instructions and commands.

So, I will not divert this series to deal with how to properly set up a Git-based version control system. In brief, one needs to establish a Git repository, and on Windows set up a Git client and then (for me), set up TortoiseGit if you want to work directly in Windows and the File Explorer rather than from the command line. In the process of doing all of this, you will also need to set up a key-based access control system with PuTTy (puttygen) so that you can communicate securely between your remote instance and your local file system. These steps are more effectively described in the TortoiseGit manual or various tutorials of one aspect or another. Installation, too, can be difficult with regard to general aspects or the PuTTy keys.

The reason, of course, for accepting this set-up complexity is being able to make changes either on a local version of code or data or a remote version of the same. This is the essence of the definition of keeping systems in ‘sync’. After having worked with these systems now for some weeks, daily, I think I can offer some simple tips for how best to work with these version control systems, points which are not obvious from most written presentations:

- First, make sure both the remote and local sources are in sync (this is actually not such an easy point, and is often the point of failure and frustration. However, until this status of being in sync is met, none of the other points below are possible.) When working locally, it is good practice to ‘pull’ any changes first from the remote repository before you attempt to ‘push’ local changes back to it. If you run into problems at this initial point, you need to research and find a fix before moving on

- Remember that your version control can really only occur from the local side, where your TortoiseGit is installed. So, while changes may occur either in the remote or local repository, the control to keep things in sync will occur from the local side (TortoiseGit)

- Whether at the remote or local repository, make all needed changes there, including deleting files, adding files, or modifying files. Then, commit those changes to the repository at hand (local or remote). (On TortoiseGit locally, this is done via the ‘Add’ Explorer menu option for new files; use the ‘Check for modifications’ option for changed files.) Commitment to the repository at hand is needed before the version control system knows what has been formally modified

- Again, be cognizant of where the modifications have occurred, which in any case you will control from the local TortoiseGit. If the changes have been made locally, then ‘push’ those changes to the remote repository; if the changes have been made remotely, then ‘pull’ those changes changes back to the local.

Always make sure that as any changes are made, at either side, they are synced to the system. In this way, you can be assured that your version control system is in a stable state, and you are free to make changes on either the local or remote side. Also know you can use GitHub for keeping multiple local instances (a desktop and a laptop in my case) in sync with the remote repository. Simply follow the above guidelines for each instance.

Handling Styles (CSS)

If you recall the discussion in CWPK #15, there is a difference in where custom styles can be set when viewing notebook pages locally versus whether they are called up directly from Python. Now, as we move to an online expression of these notebooks, we again raise the question of where online custom styles can be invoked.

Perhaps in some expressions, where style overrrides can be invoked is a matter of little consequence. But this CWPK series has some specific styles in such things as pointing to warnings, pointing to online resources, etc. Having a consistent way to refer to these styles (presentation) means better efficiency.

My hope had been that with MyBinder we had some identifiable means for providing such custom.css overrides as well. Though I can see links to such in page views, and there are hints online for how to actually modify styles, I was unable to find any means for effectively doing so. My suspicion is that online interactivity such as MyBinder is still in its infancy, and the degree of control that we expect in either local or remote environments is not yet mature.

Thus, since I could find no way after many frustrating hours to provide my own specific styles, I had to make the reluctant decision to embed all such style changes in each individual notebook page. (What this means, effectively, is the specific statement of style attributes needs to be repeated each time as used [MyBinder does not support referring to a style name in a separate external file, which is the more efficient alternative].) This embedded approach is not efficient, but, like prior discussions about the use of relative addresses, sometimes being specific is the best way to ensure consistent treatment across environments.

Using MyBinder

As time has gone on, I now have learned a general workflow that reflects these realities. In general, thus, with each new CWPK installment I try to:

- Draft all material in the Jupyter Notebook; make sure that version embodies all desired content and style changes and updates

- Inspect all link references and style definitions to make sure they are absolute, and not referenced

- Make sure all external files and images are moved and stored on the repository systems

- Post the updated file to the its current repository, and then commit it

- Push the updated file to the remote (or local) repository

- Convert the

*.ipynbto HTML and post on my local blog - Mix and stir again.

Though it is not designed directly as such, it is also possible to analyze use of MyBinder and gain statistics of use.

Additional Documentation

- A basic Binder tutorial.

*.ipynb file. It may take a bit of time for the interactive option to load.