What Began as Data Integration Implies So Much More

What Began as Data Integration Implies So Much More

Oh, it was probably two or three years ago that one of our clients asked us to look into single-source authoring, or more broadly what has come to be known as COPE (create once, publish everywhere), as made prominent by Daniel Jacobson of NPR, now Netflix. We also looked closely at the question of formats and workflows that might increase efficiencies or lower costs in the quest to grab and publish content.

Then, of course, about the same time, it was becoming apparent that standard desktop and laptop screens were being augmented with smartphones and tablets. Smaller screen aspects require a different interface layout and interaction; but, writing for specific devices was a losing proposition. Responsive Web design and grid layout templates that could bridge different device aspects have now come to the fore.

Though it has been true for some time that different publishing venues — from the Web to paper documents or PDFs — have posed a challenge, these other requirements point to a broader imperative. I have intuitively felt there is a consistent thread at the core of these emerging device, use and publishing demands, but the common element has heretofore eluded me.

For years — decades, actually — I have been focused on the idea of data interoperability. My first quest was to find a model that could integrate text stories and documents with structured data from conventional databases and spreadsheets. My next quest was to find a framework that could relate context and meaning across multiple perspectives and world views. Though it took awhile, and which only began to really take shape about a decade ago, I began to focus on RDF and general semantic Web principles for providing this model.

Data integration though open, semantic Web standards has been a real beacon for how I have pursued this quest. The ideal of being able to relate disparate information from multiple sources and viewpoints to each other has been a driving motivation in my professional interests. In analyzing the benefits of a more connected world of information I could see efficiencies, reduced costs, more global understandings, and insights from previously hidden connections.

Yet here is the funny thing. I began to realize that other drivers for how to improve knowledge worker efficiencies or to deploy results to different devices and venues share the same justifications as data integration. Might there not be some common bases and logic underlying the interoperability imperative? Is not data interoperability but a part of a broader mindset? Are there some universal principles to derive from an inspection of interoperability, broadly construed?

In this article I try to follow these questions to some logical ends. This investigation raises questions and tests from the global — that is, information interoperability — to the local and practical in terms of notions such as create once, use everywhere, and have it staged for relating and interoperability. I think we see that the same motivators and arguments for relating information apply to the efficient ways to organize and publish that information. I think we also see that the idea of interoperability is systemic. Fortunately, meaningful interoperability can be achieved across-the-board today with application of the right mindsets and approaches. Below, I also try to set the predicates for how these benefits might be realized by exploring some first principles of interoperability.

What is Interoperability?

So, what is interoperability and why is it important?

So-called enterprise information integration and interoperability seem to sprout from the same basic reality. Information gets created and codifed across multiple organizations, formats, storage systems and locations. Each source of this information gets created with its own scope, perspective, language, characteristics and world view. Even in the same organization, information gets generated and characterized according to its local circumstances.

In the wild, and even within single organizations, information gets captured, represented, and characterized according to multiple formats and viewpoints. Without bridges between sources that make explicit the differences in format and interpretation, we end up with what — in fact — is today’s reality of information stovepipes. The reality of our digital information being in isolated silos and moats results in duplicate efforts, inefficiencies, and lost understandings. Despite all of the years and resources thrown at information generation, use and consumption, our digital assets are unexploited to a shocking extent. The overarching cause for this dereliction of fiscal stewardship is the lack of interoperability.

By the idea of interoperability we are getting at the concept of working together. Together means things are connected in some manner. Working means we can mesh the information across sources to do more things, or do them better or more cheaply. Interoperability does not necessarily imply integration, since our sources can reside in distributed locations and formats. What is important is not the physical location — or, indeed, even format and representations — but that we have bridges across sources that enable the source information to work together.

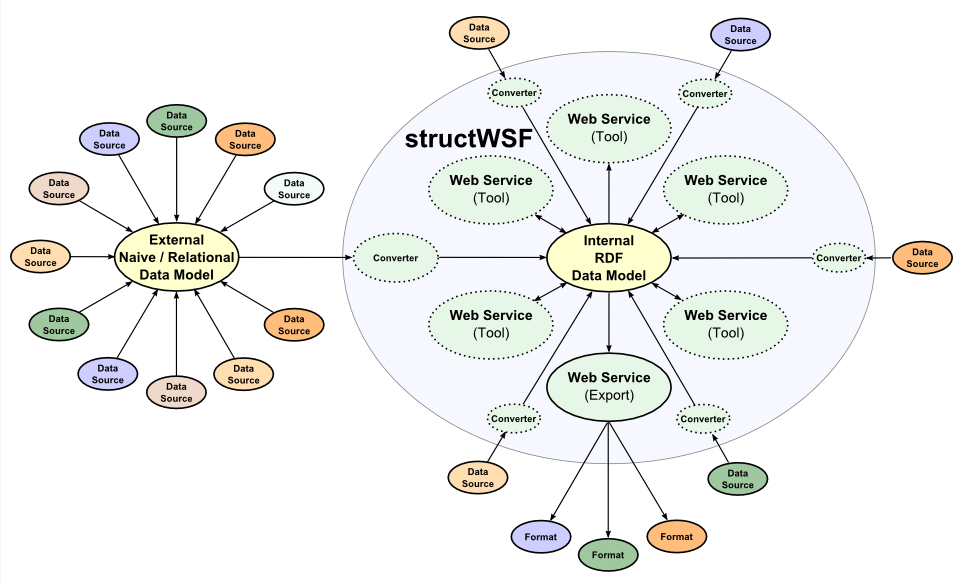

In working backwards from this observation, then, we need certain capabilities to fulfill these interoperability objectives. We need to be able to ingest multiple encodings, serializations and formats. Because we need to work with this information, and tools for doing so are diverse, we also need the ability to export information in multiple encodings, serializations and formats. Human circumstance means we need to ingest and encode this information in multiple human languages. Some of our information is more structured, and describes relationships between things or the attributes or characterizations of particular types of things. Since all of this source information has context and provenance, we need to capture these aspects as well in order to ascertain the meaning and trustworthiness of the information.

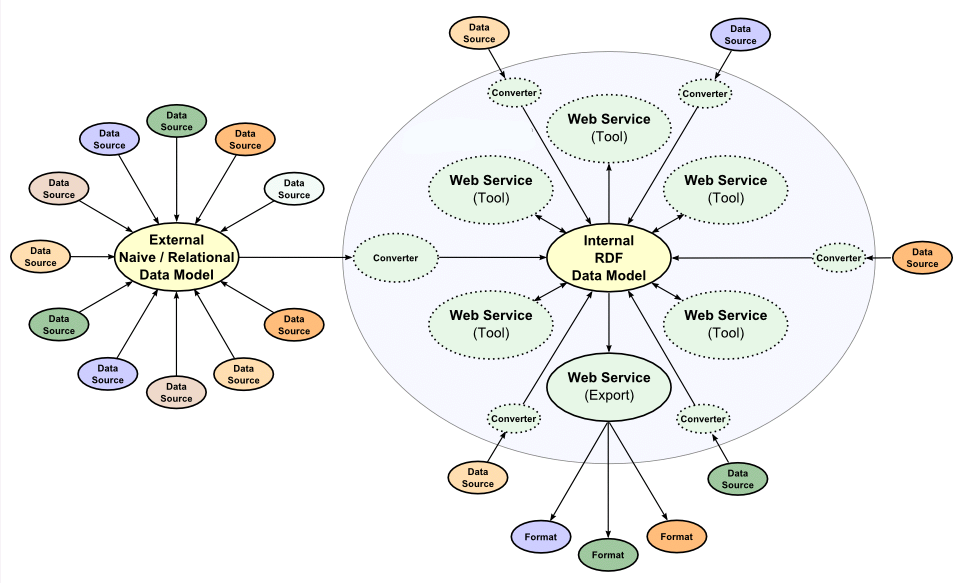

This set of requirements is a lot of work, which can most efficiently be done against one or a few canonical representations of the input information. From a data integration perspective, then, the core system to support, store and manage this information should be based on only a few central data representations and models, with many connectors for ingesting native information in the wild and tools to support the core representations:

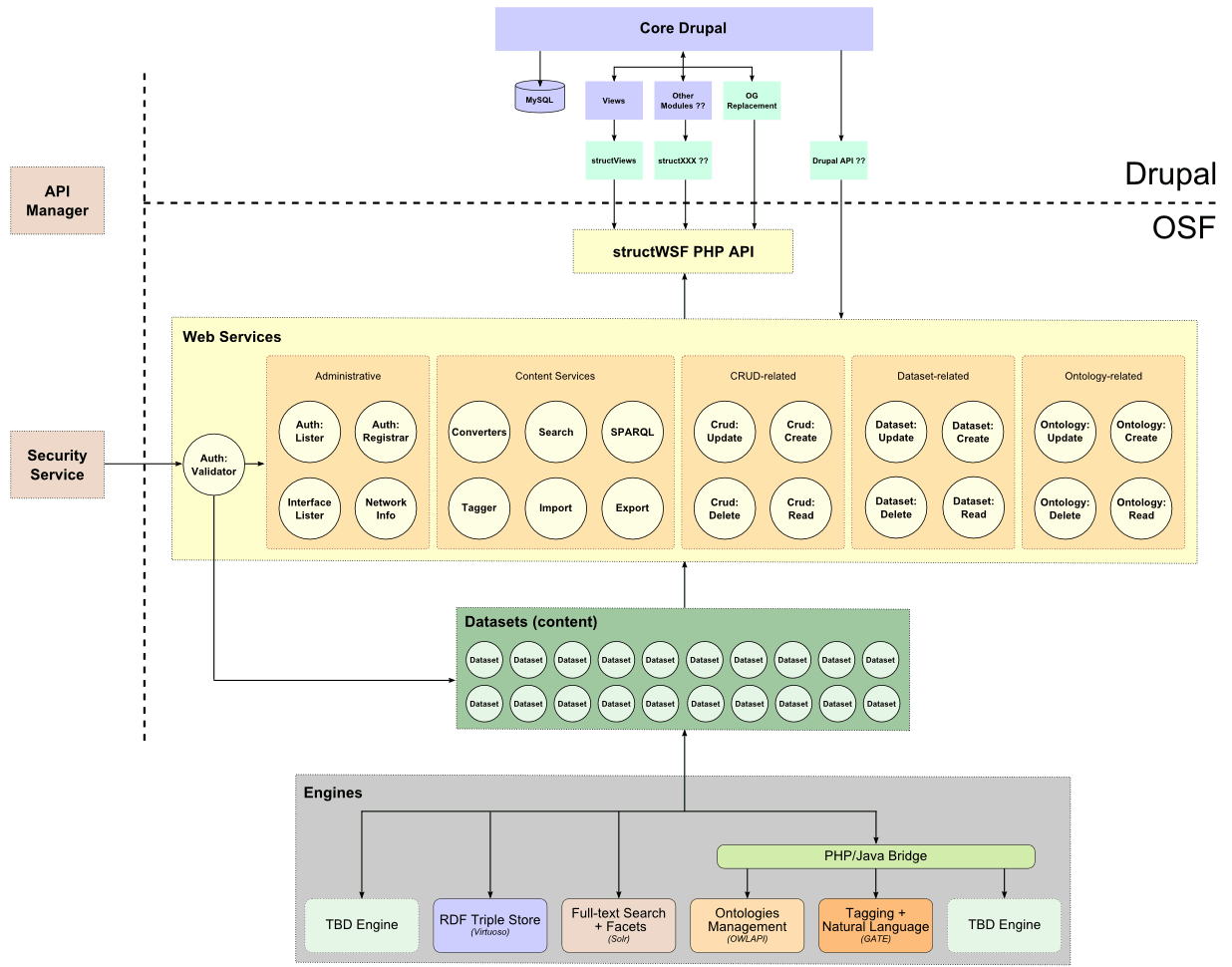

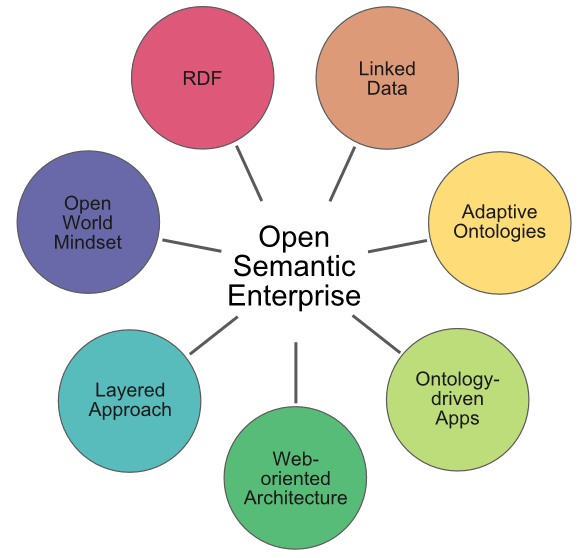

In our approach at Structured Dynamics we have chosen the Resource Description Framework (RDF) as the structured data model at the core of the system [1], supported by the Lucene text engine for full-text search and efficient facet searching. Because all of the information is given unique Web identifiers (URIs), and the whole system resides on the Web accessible via the HTTP protocol, our information may reside anywhere the Internet connects.

This gives us a data model and a uniform way to represent the input data across structured, semi-structured and unstructured sources. Further, we have a structure that can capture the relations or attributes (including metadata and provenance) of the input information. However, one more step is required to achieve data interoperability: an understanding of the context and meaning of the source information.

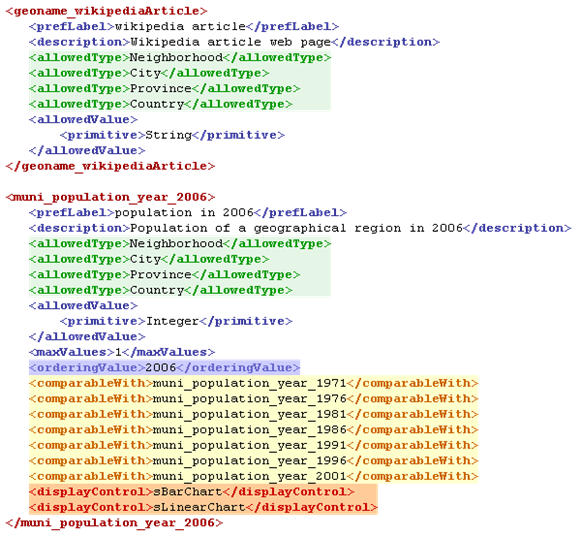

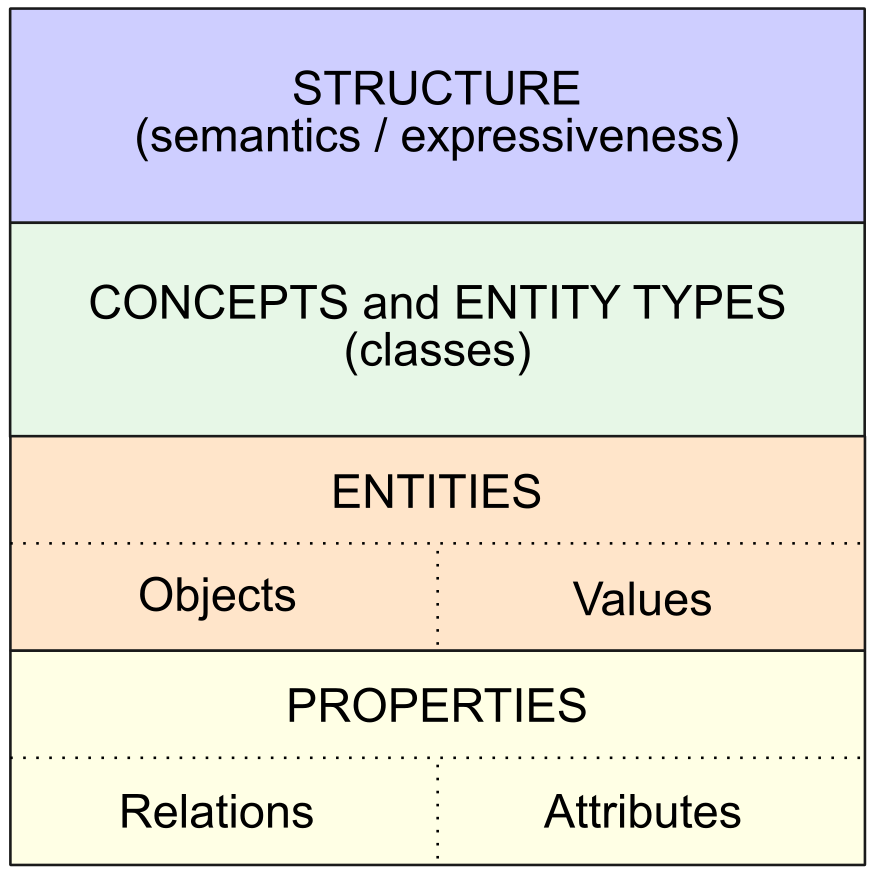

To achieve the next layer in the data interoperability pyramid [2] it is thus necessary to employ semantic technologies. The structure of the RDF data model has an inherent expressiveness to capture meaning and context. To this foundation we must add a coherent view of the concepts and entity types in our domain of interest, which also enables us to capture the entities within this system and their characteristics and relationships to other entities and concepts. These properties applied to the classes and instances in our domain of interest can be expressed as a knowledge graph, which provides the logical schema and inferential framework for our domain. This stack of semantic building blocks gets formally expressed as ontologies (the technical term for a working graph) that should putatively provide a coherent representation of the domain at hand.

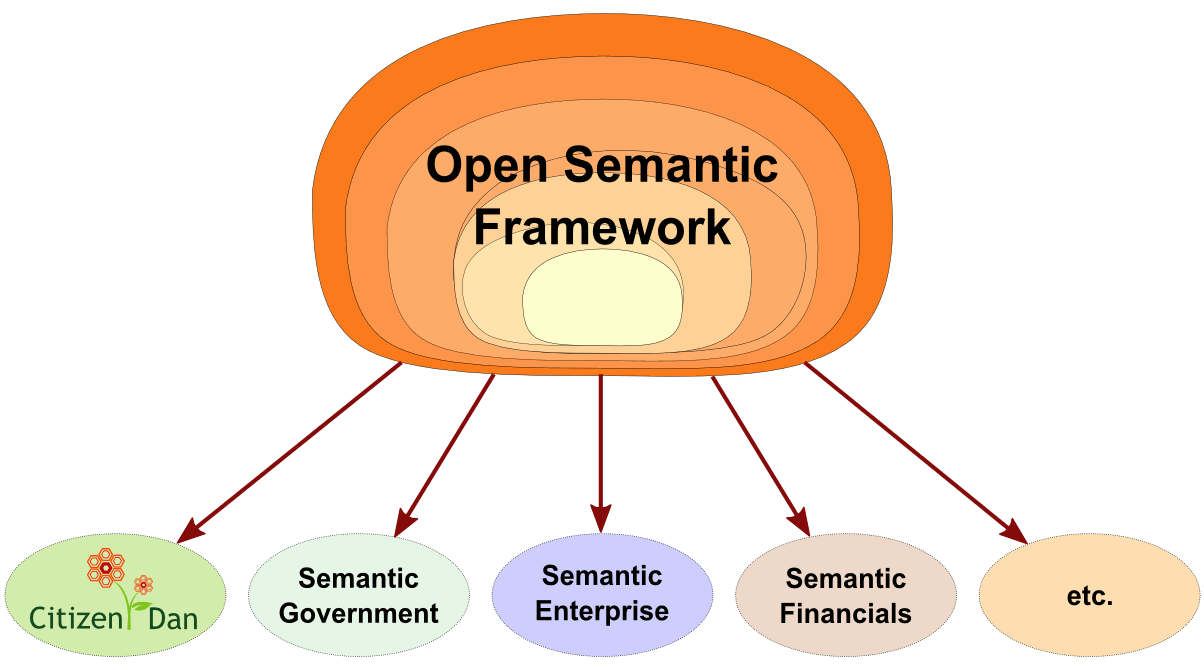

We can visualize this semantic stack as follows:

We have been using the spoke-and-hub diagram above for data flows for some years and have used the semantic stack representation before, too. I believe in my bones the importance of data interoperability to competitive advantage for enterprises, and therefore its business worth as a focus of my company’s technology. But, once so considered, some more fundamental questions emerge. What makes data interoperability a worthwhile objective? Can an understanding of those objectives bring us more fundamental understandings of fundamental benefits? Does a grounding in more fundamental benefits suggest any change in our development priorities?

Drivers of Interoperability

I think we can boil the drivers of interoperability down to four. These are:

- Efficiency — literally trillions are spent globally each year in the research, creation, re-use, publishing, storing and browsing of information [3]. Yet relevant information is hard to find, and sometimes obscure information is overlooked. The lack of reuse of prior good content because it is not discoverable is unconscionable given today’s technologies. The base productivity of information use is low;

- Cost — missed information or lack of awareness of relevant information leads to increased time, increased direct costs (labor and material), and increased indirect costs. Awareness, understanding and re-use of existing information would save millions or more for brand-name firms [3] annually if these interoperability gaps were overcome;

- Insight — drawing connections between previously unconnected things and enabling discovery are essential inputs to innovation, itself the overall driver of productivity (and, therefore, wealth) gains. The reinforcing leverage of interoperability resides in its ability to bring new understandings and insights; and

- Capture — simply being able to include the 80% of extant information contained in text is a huge first step to interoperability, but grounding the system in the inherent connectedness of the Web means that all kinds of fields + streams, APIs, mappings, DBs, datasets, Web content, on-the-fly discoveries, and device sensors through the Internet of things (IoT) can be captured to contribute to our insights.

To be sure, data interoperability is focused on insight. But data interoperability also brings efficiency and cost reductions. As we add other aspects of interoperability — say, responsive design for mobile — we may see comparatively fewer benefits in insight, but more in efficiency, cost, and, even, capture. Anything done to increase benefits from any of these drivers contributes to the net benefits and rationale for interoperability.

Principles of Interoperability

The general goodness arising from interoperability suggests it is important to understand the first principles underlying the concept. By understanding these principles, we can also tease out the fundamental areas deserving attention and improvement in our interoperability developments and efforts. These principles help us cut through the crap in order to see what is important and deserves attention.

I think the first of the first principles for interoperability is reusability. Once we have put the effort into the creation of new valuable data or content, we want to be able to use and apply that knowledge in all applicable venues. Some of this reuse might be in chunking or splitting the source information into parts that can be used and deployed for many purposes. Some of this reuse might be in repurposing the source data and content for different presentations, expressions or devices. These considerations imply the importance of storing, characterizing, structuring and retrieving information in one or a few canonical ways.

Interoperable content and forms should also aspire to an ideal of “onceness“. The ideal is that the efforts to gather, create or analyze information be done as few times as possible. This ideal clearly ties into the principle of reusabilty because that must be in place to minimize duplication and overlooking what exists. The reason to focus on onceness is that it forces an explication of the workflows and bottlenecks inherent to our current work practices. These are critical areas to attack since, unattended, such inefficiencies provide the “death by a thousand cuts” to interoperability. Onceness is at the center of such compelling ideas as COPE and the role of APIs in a flexible architecture (see below) to promote interoperability.

A respect for workflows is also a first principle, expressed in two different ways. The first way is that existing workflows can not be unduly disrupted when introducing interoperability improvements. While workflows can be improved or streamlined over time — and should — initial introduction and acceptance of new tools and practices must fit with existing ways of doing tasks in order to see adoption. Jarring changes to existing work practices are mostly resisted. The second way that workflows are a first principle is in the importance of being aware of, explicitly modeling, and then codifying how we do tasks. This becomes the “language” of our work, and helps define the tooling points or points of interaction as we merge activities from multiple disciplines in our domain. These workflow understandings also help us identify useful points for APIs in our overall interoperability architecture.

These considerations provide the rationale for assigning metadata [4] that characterize our information objects and structure, based on controlled vocabularies and relationships as established by domain and administrative ontologies [5]. In the broadest interoperability perspective, these vocabularies and the tagging of information objects with them are a first principle for ensuring how we can find and transition states of information. These vocabularies need not be complex or elaborate, but they need to be constant and consistent across the entire content lifecycle. There are backbone aspects to these vocabularies that capture the overall information workflow, as well as very specific steps for individual tasks. As a complement to such administrative ontologies, domain ontologies provide the context and meaning (semantics) for what our information is about.

The common grounding of data model and semantics means we can connect our sources of information. The properties that define the relationships between things determine the structure of our knowledge graph. Seeking commonalities for how our information sources relate to one another helps provide a coherent graph for drawing inferences. How we describe our entities with attributes provides a second type of property. Attribute profiles are also a good signal for testing entity relatedness. Properties — either relations or attributes — provide another filter to draw insight from available information.

If the above sounds like a dynamic and fluid environment, you would be right. Ultimately, interoperability is a knowledge challenge in a technology environment that is rapidly changing. New facts, perspectives, devices and circumstances are constantly arising. For these very reasons an interoperability framework must embrace the open world assumption [6], wherein the underlying logic structure and its vocabulary and data can be grown and extended at will. We are seeing some breakaway from conventional closed-world thinking of relational databases with NoSQL and graph databases, but a coherent logic based on description logics, such as is found with open standard semantic technologies like RDF and OWL and SPARQL, is even more responsive.

Though perhaps not quite at the level of a first principle, I also think interoperability improvements should be easy to use, easy to share, and easy to learn. Tooling is clearly implied in this, but also it is important we be able to develop a language and framing for what constitutes interoperability. We need to be able to talk about and inspect the question of interoperability in order to discover insights and gain efficiencies.

Aspects of Interoperability

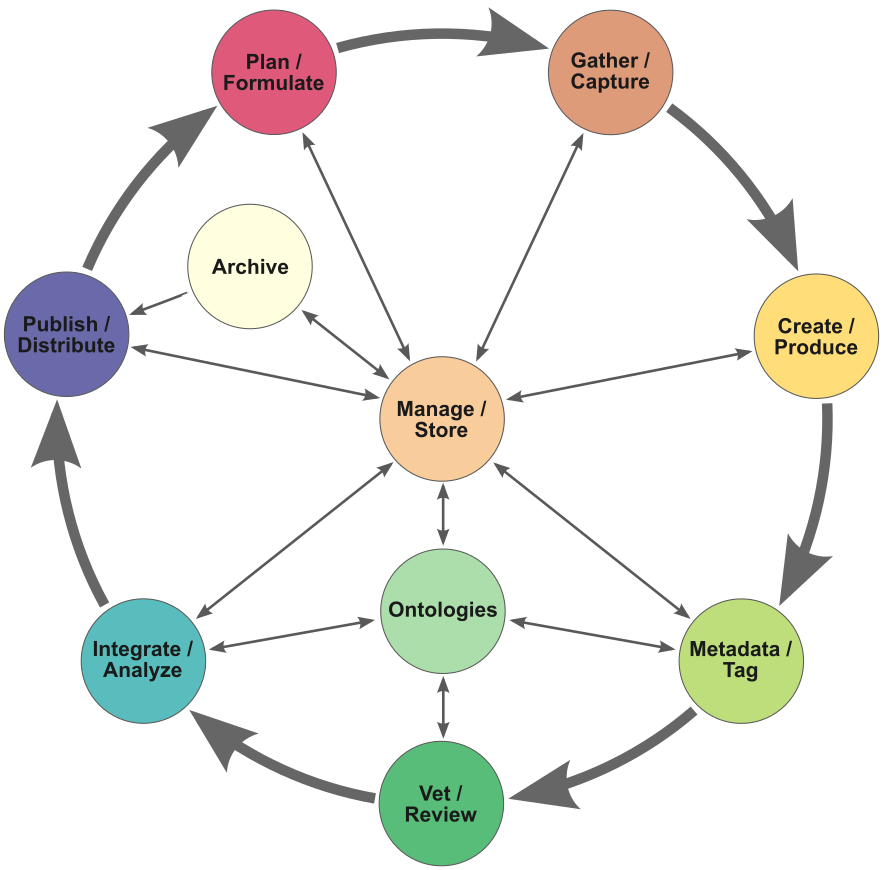

The thing about interoperability is that it extends over all aspects of the information lifecycle, from capturing and creating information, to characterizing and vetting it, to analyzing it, or publishing or distributing it. Eventually, information and content already developed becomes input to new plans or requirements. These aspects extend across multiple individuals and departments and even organizations, with portions of the lifecycle governed (or not) by their own set of tools and practices. We can envision this overall interoperability workflow something like the following [7]:

Overall, only pieces of this cycle are represented in most daily workflows. Actually, in daily work, parts of this workflow are much more detailed and involved than what this simplistic overview implies. Editorial review and approvals, or database administration and management, or citation gathering or reference checking, or data cleaning, or ontology creation and management, or ETL activities, or hundreds of other specific tasks, sit astride this general backbone.

Besides showing that interoperability is a systemic activity for any organization (or should be), we can also derive a couple of other insights from this figure. First, we can see that some form of canonical representation and management is central to interoperability. As noted, this need not be a central storage system, but can be distributed using Web identifiers (URIs) and protocols (HTTP). Second, we characterize and tag our information objects using ontologies, both from structural and administrative viewpoints, but also by domain and meaning. Characterizing our information by a common semantics of meaning enables us to combine and analyze our information.

A third insight is that a global schema specific to workflows and information interoperability is the key for linking and combining activities at any point within the cycle. A common vocabulary for stages and interoperability tasks, included as a best practice for our standard tagging efforts, provides the conventions for how batons can get passed between activities at any stage in this cycle. The challenge of making this insight operational is one more of practice and governance than of technology. Inspecting and characterizing our information workflows with a common vocabulary and understanding needs to be a purposeful activity in its own right, backed with appropriate management attention and incentives.

A final insight is that such a perspective on interoperability is a bit of a fractal. As we get more specific in our workflows and activities, we can apply these same insights in order to help those new, more specific workflows become interoperable. We can learn where to plug into this structure. And, we can learn how our specific activities through the application of explicit metadata and tags with canonical representations can work to interact well with other aspects of the content lifecycle.

Interoperability can be achieved today with the right mindsets and approaches. Fortunately, because of the open world first principle, this challenge can be tackled in an incremental, piecemeal manner. While the overall framework provides guidance for where comprehensive efforts across the organization may go, we can also cleave off only parts of this cycle for immediate attention, following a “pay as you benefit” approach [8]. A global schema and a consistent approach to workflows and information characterizations can help ensure the baton is properly passed as we extend our interoperability guidance to other reaches of the enterprise.

General Architecture and a Sample Path

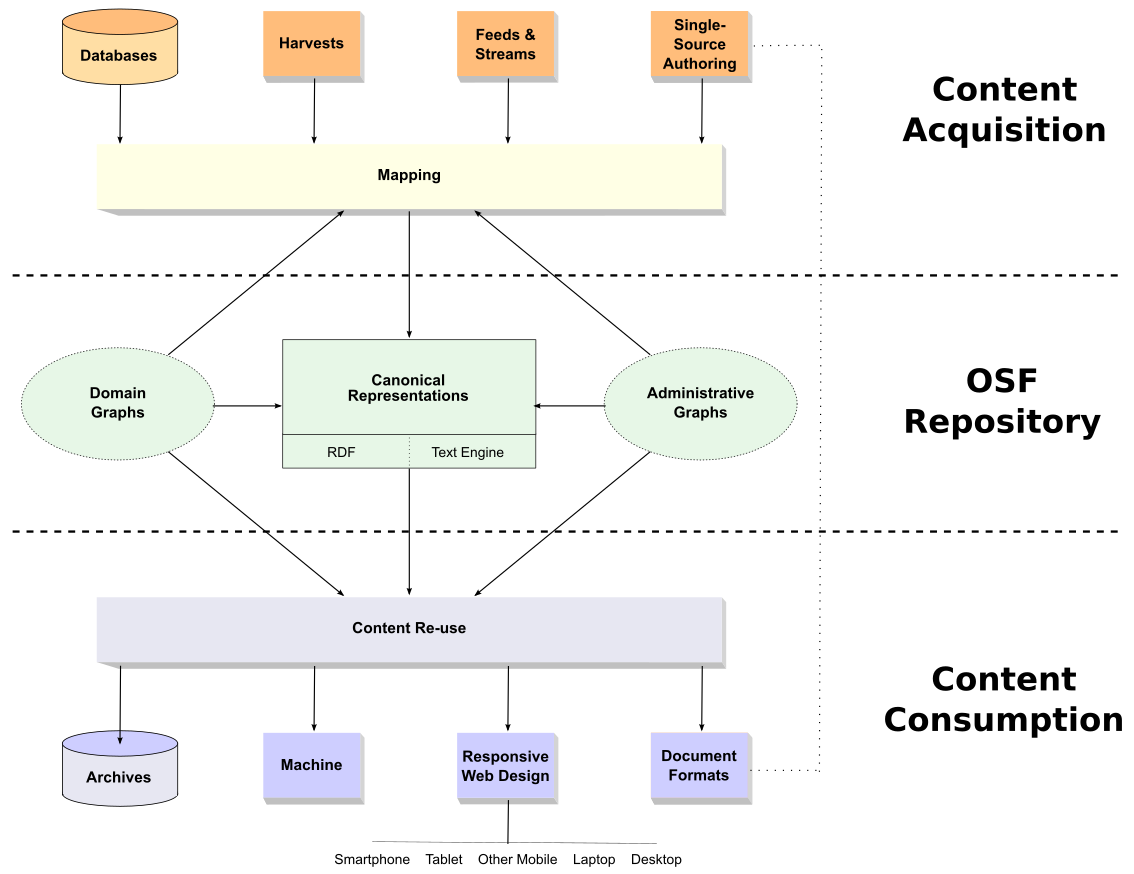

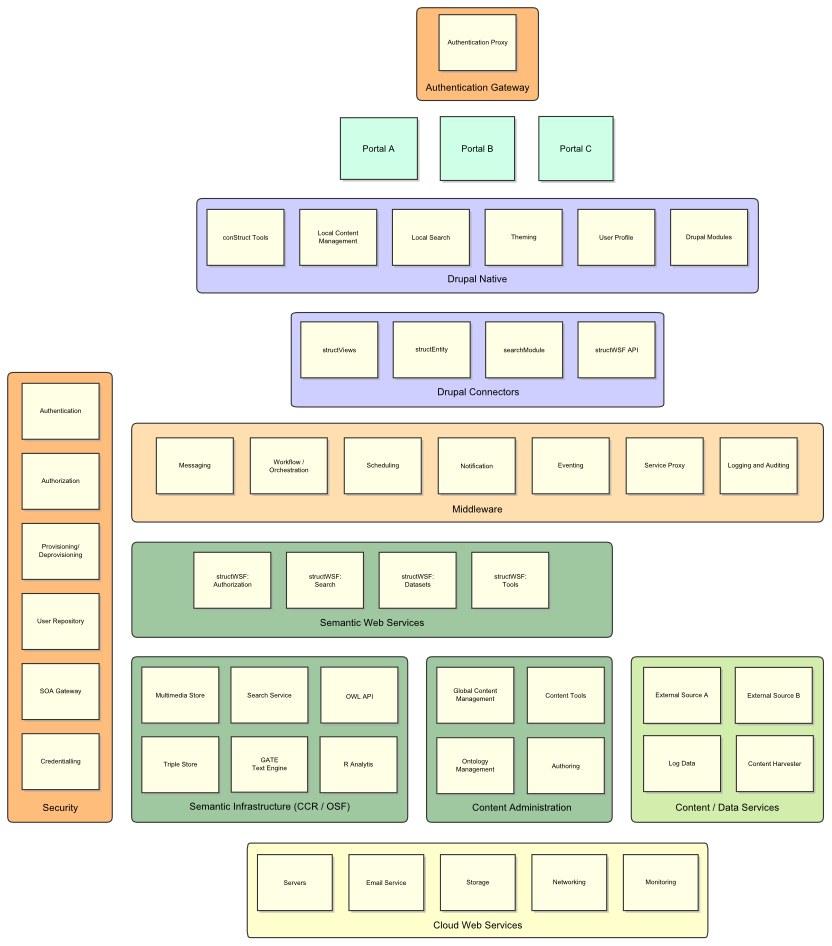

We can provide a similar high-level view for what an enterprise information architecture supporting interoperability might look like. We can broadly layer this architecture into content acquisition, representation and repository, and content consumption:

Content of all forms — structured, semi-structured and unstructured — is brought into the system and tagged or mapped into the governing domain or administrative schema. Text content is marked up with reduced versions of HTML (such as RASH [9] or Markdown [10]) in order to retain the author’s voice and intent in areas such as emphasis, titles or section headers; the structure of the content is also characterized by patterned areas such as abstracts, body and references. All structured data is characterized according to the RDF data model, with vocabularies as provided by OWL in some cases.

We already have an exemplar repository in the Open Semantic Framework [11] that shows the way (along with other possible riffs on this theme) for how just a few common representations and conventions can work to distribute both schema and information (data) across a potentially distributed network. Further, by not stopping at the water’s edge of data interoperability, we can also embrace further, structural characterization of our content. Adding this wrinkle enables us to efficiently support a variety of venues for content consumption simultaneously.

This architecture is quite consistent with what is known as WOA (for Web-oriented architecture) [12]. Like the Internet itself, WOA has the advantage of being scalable and distributed, all (mostly) based on open standards. The interfaces between architectural components are also provided though mostly RESTful application programming interfaces (APIs), which extends interoperability to outside systems and provides flexibility for swapping in new features or functionality as new components or developments arise. Under this design, all components and engines become in effect “black boxes”, with information exchange via standard vocabularies and formats using APIs as the interface for interoperability.

A Global Context for Interoperability

Though data interoperability is a large and central piece, I hope I have demonstrated that interoperability is a much broader and far-reaching concept. We can see that “global interoperability” extends into all aspects of the information lifecycle. By expanding our viewpoint of what constitutes interoperability, we have discovered some more general principles and mindsets that can promise efficiencies, lower costs and greater insights across the enterprise.

An explicit attention to workflows and common vocabularies for those flows and the information objects they govern is a key to a more general understanding of interoperability and the realization of its benefits. Putting this kind of infrastructure in place is also a prerequisite to greater tooling and automation in processing information.

We can already put in place chains of tooling and workflows governed by these common vocabularies and canonical representations to achieve a degree of this interoperability. We do not need to tackle the whole enchilada at once or mount some form of “big bang” initiative. We can start piecemeal, and expand as we benefit. The biggest gaps remain codification of workflows in relation to the overall information lifecycle, and the application of taggers to provide the workflow and structure metadata at each stage in the cycle. Again, these are not matters so much of technology or tooling, but policy and information governance.

What I have outlined here provides the basic scaffolding for how such an infrastructure to promote interoperability may evolve. We know how we do our current tasks; we need to understand and codify those workflows. Then, we need to express our processing of information at any point along the content lifecycle. A number of years back I discussed climbing the data interoperability pyramid [2]. We have made much progress over the past five years and stand ready to take our emphasis on interoperability to the next level.

To be sure there is much additional tooling still needed, mostly in the form of mappers and taggers. But the basic principles, core concepts and backbone tools for supporting greater interoperability are known and relatively easy to put in place. Embracing the mindset and inculcating this process into our general information management routines is the next challenge. Working to obtain the ideal is doable today.

PDFs available from their main pages.

PDFs available from their main pages.

Conventional IT Systems are Poorly Suited to Knowledge Applications

Conventional IT Systems are Poorly Suited to Knowledge Applications

The Time and Technology is Here to Stand Software Engineering on its Head

The Time and Technology is Here to Stand Software Engineering on its Head