Some Thoughts on SD’s Gestation of Civic Dynamics

Some Thoughts on SD’s Gestation of Civic Dynamics

Structured Dynamics (SD) announced yesterday that, in association with its partner Buzzr, it was spinning off a new software company, Civic Dynamics Inc., headquartered in Québec City, Canada. Included in the launch was the introduction of the new company’s Civic Dynamics Platform. CDP is open-source software and supporting systems to assist municipalities to publish dynamic open government data, and to provide citizens a set of tools for viewing, searching, filtering and analyzing that data.

The announcements of those releases stand on their own. My purpose is not to duplicate them. Rather, now that the efforts needed for the new launch are behind us, I wanted to reflect on why and how such a spin off occurred in the first place. I think these reflections offer some insight into imperatives that face new software ventures, especially those geared to enterprise IT.

A Bit of History

It was just about five years ago that Fred Giasson and I began Structured Dynamics. (This was also after a year working together at Zitigist under the sponsorship of OpenLink Software.) Our mission at SD’s inception was to create a workable platform for bringing semantic technology capabilities to enterprises. Our specific interest was in using semantic technologies and RDF to solve the decades-old challenge of information interoperability in larger organizations. By serendipity, we were able to secure an enterprise client on virtually the first day we started SD. That forced us to grapple immediately with the then current woeful state of semantic technologies for enterprises.

We observed a number of problems at that time. Here is a short list of some of those problems from five years ago, and brief statements of what we initiated to address them:

- Search — native triple stores at that time were not performant in search, and none captured the full text of documents. Further, semantic search offers unique opportunities in structure and inference. As a result, we were one of the first to adopt Solr for semantic technologies

- Portal framework — there was a (general) absence of portal front ends that met acceptance in the marketplace. We evaluated and chose Drupal; over time a design choice to have loose coupling with Drupal has transitioned to become more integrated

- CRUD — basic database management capabilities, such as create, read, update or delete, were not often exposed at the application level. Our choice here was to decouple this access and adopt a distributed design by embracing RESTful web services, endpoints and APIs, all of which were geared to provide a universal abstraction for dealing with all data engines (as colllectively expressed as a “repository”)

- Architecture — though complete frameworks had been put forward, mostly by academic researchers, most had short lives and all lacked basic enterprise capabilities. We designed an architecture that favored integration and expansion — largely though APIs — while leveraging existing components. We also at this time made a commitment to open-source for all key components of the architecture

- Stack — there were no complete software (deployment) stacks. Creating one required fragmented piece parts with gaps; and there certainly were not standard deployment or installation abilities. Much of SD’s effort over the past five years has been addressing this gap

- Access control (security) — virtually all enterprises need to control access to privileged information, and no security existed five years ago for semantic applications. In the early versions of the Open Semantic Framework, the foundation to Civic Dynamics’ CDP platform, we used a simple IP authorization approach based on the interaction of tool (endpoint), dataset and role. Subsequently we have established middleware integrations with third-party security and key-based permission mechanisms when OSF is used standalone

- Version control — any enterprise content system or repository must also have ways to track revisions and enforce version control. Early semantic technologies completely lacked these considerations. OSF has made progress in integrating with the Drupal revisioning system and in establishing middleware methods for interfacing with third-party version control systems

- Workflow support — managing enterprise content in general, and more specifically managing the semantic aspects of integration, requires formal workflow and governance procedures. However, historically, and up to and including today, there is zero workflow support in semantic technologies. In fact, there is virtually no discussion of this topic at all. We are only at the beginning stages of incorporating formal workflow methods into OSF. We have development methodologies and best practices, though, and have identified suitable workflow engines to extend the system with formal workflow methods

- Data ingest — five years ago there was little recognition that data in the wild would not be compliant with W3C standards nor RDF, and as a result demo systems lacked ingest capabilties for legacy information, particularly enterprise database info. OpenLink Software and its Virtuoso system (one of the core engines in OSF) did, however, recognize this need. The OSF design has very much followed this approach of using “converters” or “RDFizers” for getting all wild data forms into a canonical RDF basis internal to the system

- Reference vocabularies — the ultimate means of integrating enterprise information to achieve interoperability is premised on semantic approaches and technologies. Yet, apart from some minor vocabularies, there were no suitable vocabularies five years ago in many areas. We have constructed and supported an across-domain reference vocabulary (UMBEL) and a means of representing instance data and records (irON) since then to redress these gaps

- Tooling — the means to design, manage, and test components of a semantic enterprise stack were nearly totally lacking, since most early semantic efforts were of proofs-of-concept and not production-grade systems. The areas of ontology design and maintenance were (and stilll somewhat are) weak. We have since developed many new tools, some geared at the user level, with administrator and developer tools including test suites, command-line utilities, and automated installers

- Templates, widgets and visualization — the highly structured nature of RDF data lends itself well to templating records by type, page layouts by type, and widgets by type, which may be further leveraged using inheritance and inference. The recognition of the role of semantic technologies as publishing platforms did not exist five years ago. Our response has been to develop a template inheritance system and semantic data-driven widgets. Our earliest widgets were based on Flash; the libraries are now migrating to JavaScript (d3.js) and HTML5

- Lack of documentation — lack of documentation is the bane of most open source projects, and early semantic technologies were most often developed for academic theses or as proofs-of-concept. As a result, documentation of use to practitioners and administrators was totally lacking. SD has made a concerted commitment to improved and complete documentation. Our OSF wiki with its nearly 500 technical and metholodogy articles and accompanying images is one expression of that commitment

- Lack of enterprise rigor — across all of these fronts, early semantic technologies were clearly not designed and developed with enterprise objectives and use cases in mind. SD’s overall commitment has been to rectify this gap.

What we did have five years ago was a growing list of (often) unproven open standards (principally those from the W3C) and a large roster of prototype and research tools [1], most from the academic community. Still, there were some proven engines suitable to a semantic stack (most adopted as core to the Open Semantic Framework), so there were building blocks upon which a complete framework could be based. With the right design and architecture, and appropriate “glue” to tie it all together, it appeared quite feasible to create a working semantic stack suitable for enteprise use. Multi-component, open-source packages — ranging from Alfresco to Talend or Pentaho — were showing the path to such next-generation platforms.

With the development model of an integrated semantic technology stack based on open source components and consistent “glue” in mind, we could then turn our attention to the business model and strategy behind the nascent Open Semantic Framework.

The Business Philosophy

I don’t speak much about my prior ventures because, well, they are in the past. But I have financed ventures via angel funding, venture capital, grants and client revenues. I also have background in ventures ranging across many aspects of enterprise (mostly) and consumer (less so) software.

Our funding prejudice in starting SD was to be self-financed via clients. A customer focus keeps one from getting too abstract or falling in love with innovations for which there may not be a real market. Revenue financing also means that we need not alter business strategy or approach based on a financier’s perspective. Customers call the shots; not the money interests. This funding prejudice has kept us market focused and, as a consequence, profitable since day one.

Our staffing prejudice was to not hire, at least during the framework development phase. Setting the vision for a framework is not a democratic activity, and every hire means less development productivity. To fulfill, we have partnered and employed consultants and sub-contractors, but have not diluted our own efforts in managing employees. We could stay focused by feeding only our own mouths and our vision.

Such narrow bandwidth also carries other implications. We could not take on too many clients at a given time. We needed to be extremely productive and leveraged, finding opportunities wherever we could to re-purpose prior writings or reusing or generalizing code. We also needed to be quite selective in what projects and what clients we chose. When attempting to make progress on a new platform, it is important to not become simply a contract fulfillment shop. Customers have many options for IT contracting or outsourcing; platform development and growth requires a certain self-selection by clients.

Our standard contract emphasizes that (most) efforts are intended to be open source, and our intellectual property clauses make that explicit. At first we did not know how the market might react to this insistence. For prospects serious enough to commit monies to us, however, we have found a good appreciation that open source leads to lower current project costs because the client is leveraging what has already been developed before. It seems only fair that new developments should also be made available to later customers, as well. Some of our prior clients are now seeing the lower costs and benefits by leveraging intermediate work in upgrading to latest versions and functionality.

Our fulfillment prejudice has been to complete work on time and under budget, document and train the customer in the work, and move on. Though we know they are profitable and a bread-and-butter for most enterprise vendors, we have not sought recurring annuities from our clients in maintenance fees. By keeping our eye squarely on successful tech transfer, we are disciplining ourselves to document as we go, provide tooling and support infrastructure as well as application software, and to find efficiencies in fulfillment. Meanwhile, we are able to progress rapidly on our overall development roadmap without getting bogged down in handholding. We would rather teach the customer how to fish, rather than doing the fishing for them.

Of course, not all enterprises understand or embrace these philosophies. That is fine under our development approach where market understanding and refinements are the drivers of decisions, not maximizing revenues for an increasingly growing staff count. We have been blessed to have new clients arise whenever they are needed, and to be real partners with us in furthering the vision. We have actively rejected some customer prospects because the philosophical fit was not good. We have also actively weaned ourselves from some engagements by insisting on sunsets for our support and encouraging more tech transfer and training.

These prejudices may change as we see the underlying Open Semantic Framework nearing fulfillment of its development vision. But, for an open source platform in a hurry (even considering it has been five years!), we believe these philosophies have served us and our clients well.

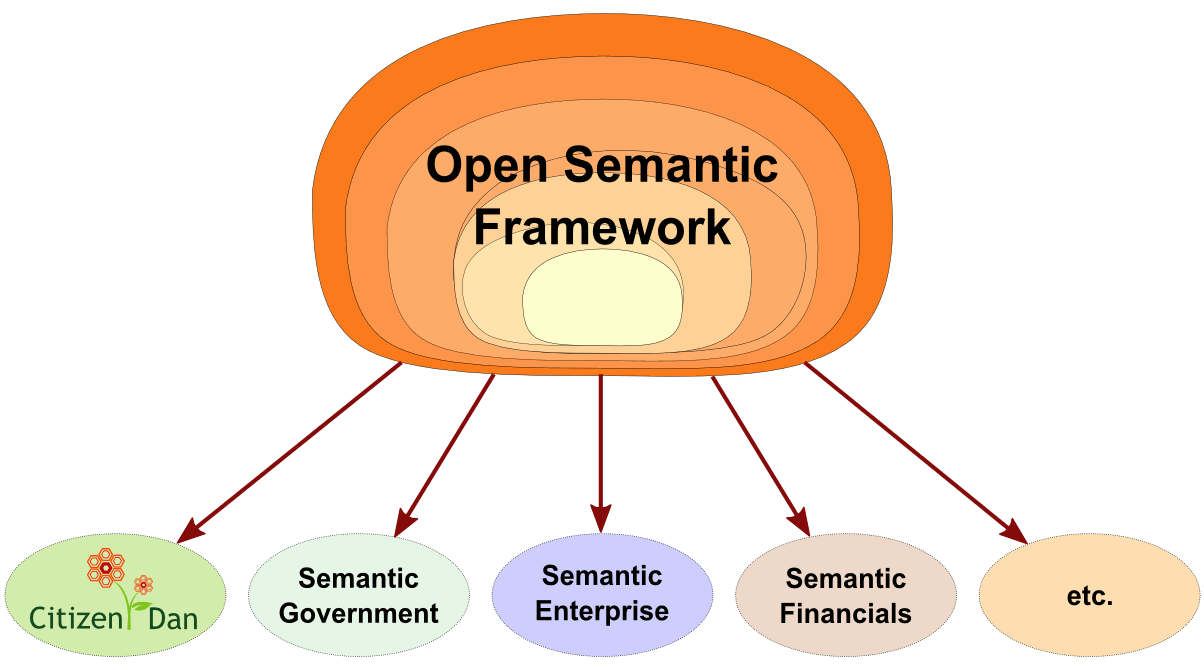

An Emphasis on the Open Semantic Framework

The net outcome for the Open Semantic Framework has been to emphasize a generic, enterprise-ready design that can be rapidly embraced and adopted by multiple markets. We have called OSF a platform of ontology-driven applications. ODapps are modular, generic software applications designed to operate in accordance with the specifications contained in one or more ontologies. ODapps fulfill specific generic tasks. Examples of current ontology-driven apps include imports and exports in various formats, dataset creation and management, data record creation and management, reporting, browsing, searching, data visualization and manipulation, user access rights and permissions, and similar. These applications provide their specific functionality in response to the specifications in the ontologies fed to them.

The ODapp vision underlying the design of OSF means we can leverage an architecture of generic tools to respond to virtually any knowledge application or any enterprise domain. The basic idea is shown by this diagram, which we first published about three years ago:

(click for full size)

In the five years of development of OSF, now at version 3.x (recently announced), we have had the good fortune to have clients and uses in publishing, tech transfer of R&D, group collaboration, health, automotive, air traffic control, sustainability, community indicators and local government. Demand in the latter two areas has been particularly strong. The strength of that market interest was the source of the dilemma for Structured Dynamics.

Unique Demands of Municipal Markets

The idea of rapid and nimble development of a new platform — especially one expressly designed to be generic across multiple domains — does not readily square with focusing on a specific market segment. This disconnect is particularly true for quite unique markets, as is the case for local governments.

In a past life I spent nearly ten years working for a trade association that represents municipally-owned electric utilities. APPA has members ranging from huge municipalities such as Los Angeles, Toronto, Seattle and San Antonio, to the smallest towns and burgs of the plains of North America. In my former role running the R&D and technical programs for this association, I personally interacted with hundreds of these wide-ranging individual communities.

In the larger communities, the electric utilities were separate departments from the local government per se, and were directed by professional utility managers. But for mid-size and smaller communities, there was often close interaction with all municipal departments.

Though sales lead times are long for all enterprise markets, they are particularly long and (often political) in government. Budgets are perennially tight. Budgets need to be proposed, argued with councils and management, and approved before work can begin. Staff are stretched across multiple functions, so use and maintenance are key factors as are concerns about longer-term support contracts. Portals and Web sites must serve all constituencies and content and tone need to be suitable to taxpayer-supported venues. Yet, because of the number and diversity of communities [2], across the entire market there is surprising innovation and experimentation. Finding better ways to do more with less is a key motivator in the local government market.

Specifically, in our own use of OSF in this market, we also observed some other unique aspects related to open data and Web sites. What constitutes open data and whether and how to make it “open” varies widely by community. Capturing local needs and perspectives often leads to comparatively high costs in theming and customizing the Web sites. The lack of dedicated and trained staff to care and feed a new Web site is always a challenge.

Structured Dynamics, with its generic platform interests and avoidance of staffing, is clearly not the right vehicle to pursue this market. Specific focus on the unique aspects of the local government market is required, plus modifications and specializationis of the platform to address government needs. Possible integration or incorporation of standard local government Web site(s) may also be required. Though we were seeing keen interest from this market, in order to address it properly a different vehicle with different venture imperatives was necessary.

Doing Justice to the Local Government Market

Early on, our good colleague and friend, Steve Ardire, helped point out some gaps in our business development. We saw that three things were missing within Structured Dynamics itself to do the local government and open government data markets justice. First, we needed a dedicated company to focus solely on this market. Second, we needed an executive familiar with the OSF platform and municipal government to head the effort. And, third, we somehow needed a way to overcome the time and costs associated with tailoring the portal for local community needs.

It was actually the last of these things that showed the first solution. We were approached about eighteen months ago by Ed Sussman, the CEO of Buzzr, about possibilities of partnering for the local government market. Buzzr has a one-click solution to theming and customizing individual Web portals, buillt around the Drupal content management system (CMS). Buzzr, a NYC-based company, has impeccable Drupal chops, having been co-founded by one of the leading Drupal shops, Lullabot. Buzzr has proven the applicability of their approach to specific verticals, including retail and education. The fact that Buzzr found us and saw a good fit for the municipal market was a formative discussion. We welcomed Buzzr’s outreach because their approach squarely addresses one of the cost and effort sticking points we were observing.

When Ed first contacted us, the OSF platform was still not sufficiently mature to be a market foundation. We needed more time to refine the platform, as well as to gain more market insight from use and use cases. Fortunately, Ed and Buzzr kept their interest strong while we refined things in the background. By the time we were able to address the other missing items, Buzzr was there to partner with us on the new venture.

Our second requirement was met by hiring Kelly Goldstrand, formerly the project manager for the NOW (Neighbourhoods of Winnipeg) portal, to head up the venture’s business development. NOW is one of the flagship installations of OSF. Her career focus has been on service planning, delivery and evaluation in the area of community health, protection and development. Kelly has significant management experience in local government and clearly understood OSF; her guidance had been pivotal in much of the system’s functionality. Kelly also has a proven track record in mentoring projects through local approvals and training city staff in use and maintenance of new technologies. After early retirement Kelly was ready to consider our opportunity and then graciously agreed to join us.

The last piece of the puzzle was forming the new venture. We had been working with the Civic Dynamics name for some time, and had also played around a bit with logo and Web site. Once the other things fell into place, we incorporated Civic Dynamics, Inc. in Québec (where it is also known as Dynamique Civique), given the strong market interest shown in Canada to date, and began preparing for the formal launch of the venture. We also needed to await the completion of OSF v 3.0.

A Report Card on SD’s Multi-year Plan

It now appears likely that the five-year plan we set for ourselves at the founding of Structured Dynamics may actually take six to seven years to achieve. This time extension derives from the realities of our client work over this time frame. One reality is that client-specific needs have caused us to necessarily divert from our own internal development path. Not all development can contribute to fulfilling a generic platform. Every client has unique needs and circumstances that are not generalizable to others. A second reality is that only through real client engagements can market requirements be truly discerned. Customer-centric development is absolutely essential to keep software grounded.

Meanwhile, Back at Civic Dynamics

We are as curious as the next person to see whether a dedicated spin-off is the right way to handle a specific vertical market. It will also be interesting to see how coordination and support can best be provided between the dynamics duo (Structured and Civics).

Nonetheless, we are excited about finally getting postured to pursue the growing market for open, local government data. We’d like to thank Kelly and Ed and all of our original sponsors for helping to gestate the venture to this point. Now that it has been birthed, we hope to nurture it and get it on its own two feet as soon as possible. Before we know it, and assuming we’ve raised it properly, Civic Dynamics will be celebrating its own life events!

Nice post Mike and congrats on Civic Dynamics

@sardire